“To resist a tyrant is not to resist God, nor yet his ordinance.” John Knox, 1564

“Resistance theory”

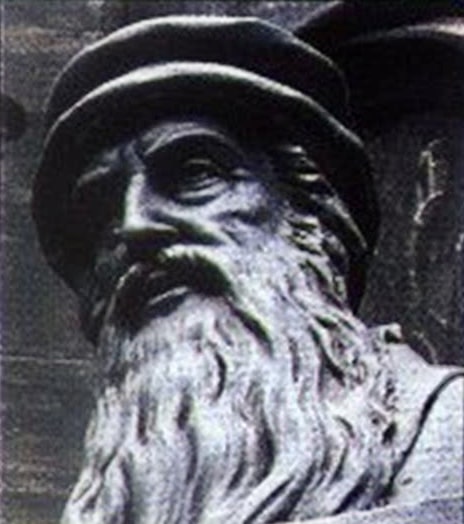

Many have wrestled with the idea of resistance to tyranny, including John Knox.

This is a concept discussed in areas such as political philosophy and church history. It has to do with various questions, including: Should the ruling powers ever be resisted? Is resistance to tyranny ever justifiable? Can an individual or a group defy governments or heads of states? When is this permissible, and for what reasons? Who can be involved in such resistance?

These sorts of questions have especially been asked by many folks over the past year, since so many governments have resorted to very draconian and often disproportionate actions in dealing with the corona virus. Various lockdowns, shutdowns, and infringements on individual freedoms and liberties – and even on basic human rights – have reignited discussions about how far governments can go, and how much the citizenry must submit to state mandates, laws and rules.

But such questions are not new – there is historical basis for all this as well. Many were thinking about such matters quite deeply during the period of the development of the modern nation state in Europe, and during the various Protestant Reformations. Reformers like Luther, Calvin and others looked at these topics in the light of Scripture, and in the context of the political and ecclesiastical situations of the day. I hope to pen pieces on their thoughts on this in the days ahead.

All this was not just theoretical, but involved very practical realities of the day. That was certainly the case with John Knox and the Scottish Reformation. He was very much involved in thinking and writing about such matters. And like many, he suffered quite a bit as he worked out in practice his thoughts on these issues.

As such, some of his writings and actions are worth looking at here, albeit rather briefly. Let me start with a quick timeline of his life:

1513 or 1514 Born in Haddington, Scotland.

1536 Graduates from St Andrews University.

1540 He is ordained a priest.

1545 Knox had by now embraced Reformation beliefs.

1546 The reformed preacher George Wishart is burned at the stake. Knox had met him shortly prior to this.

1547 Joins in a failed Protestant rebellion in St. Andrews.

July 1547 He is made a galley slave on a French ship.

February 1549 He is released after spending 19 months in the galley-prison.

1549-1559 He spends a decade living in exile, including in Geneva and Frankfurt.

April 1550 The Magdeburg Confession appears, a Lutheran tract outlining the place for resistance to authority by lesser magistrates.

1553 Mary Tudor becomes Queen in England.

July 1556 Knox goes to Calvin’s Geneva.

1558 First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women appears.

1558 An Appellation to the Nobility and Estates of Scotland appears.

May 1559 He arrives back in Scotland.

July 1560 The Queen Regent, Mary of Guise, dies in Edinburgh.

August 1560 The Scottish Parliament ratifies The Scots Confession, establishing Protestantism as the religion of the state.

1561 He writes the Book of Discipline.

August 1561 Mary Queen of Scots arrives in Scotland.

1564 A Defense of the Biblical Doctrine of Resistance to Wicked and Tyrannical Civil Magistrates is published.

1567 Mary abdicates and is sent to prison soon afterwards.

July 1567 James VI crowned king of Scotland.

1571 He has to flee Edinburgh as civil strife continues.

1572 Knox dies.

The two 1558 publications mentioned above are where we find much of his thoughts on resistance. The First Blast was not an anti-woman work as such, but was concerned much more specifically with the several female rulers who at the time were bringing so much grievous persecution upon Protestants – specifically Mary Tudor (“Bloody Mary”).

He wrote this while still in Geneva, and Calvin did not take a liking to it. Moreover, unfortunately, this came out just as Elizabeth 1 took the throne in England, and she was rather alarmed by it, although sympathetic to the Protestant cause.

In Appellation he sought to give a defence of Reformed doctrine. He also called for the right of armed resistance against ungodly rulers. The people have a responsibility to resist evil and evil rulers. He did not say that all people can and should resist, but he laid out general principles, based on some biblical examples.

Let me draw upon a few historical experts here. Peter Marshall’s 2017 history of the English Reformation, Heretics and Believers, speaks to these writings, and he goes on to say this:

Knox published in July 1558 the outline for an envisioned Second Blast. In it he argued that monarchs should be elected, rather than succeed by inheritance … that unfit rulers might legitimately be deposed. These were not universal, or even majority views among the exiles, let alone the more prudent evangelicals keeping their heads down at home. But in the late 1550s it was becoming more widely accepted – by Catholics as well as evangelicals – that the duty of political obedience was contingent rather than absolute, that obligations to the laws of God, or of his Church, always took precedence over merely human regulations. Christians had always known and believed this.

In his new volume Therefore the Truth I Speak, theologian Donald Macleod speaks to this matter in some detail.

He writes:

He placed the primary responsibility for resisting tyranny and suppressing idolatry firmly on ‘the Nobility and Estates of Scotland’. One reason for this would have been the influence of Calvin, who had spoken out clearly against private individuals violating the authority of magistrates, but had gone on to argue that ‘the lesser magistrates’ (‘the magistrates of the people’) were by God’s appointment protectors of their communities and therefore duty-bound to oppose ‘the fierce licentiousness of kings … who violently fall upon and assault the lowly common folk.’

But this was not just a “matter of religious freedom alone. The liberty of his country was in peril from the determination of the Queen Regent and her court, backed by a French garrison in Leith, to turn Scotland into a province of France.”

In his 1980 volume Theology and Revolution in the Scottish Reformation, Richard Greaves has a lengthy chapter on “The Legitimacy of Resistance.” He says this:

There is ample precedent in medieval political theory for Knox’s views. Kingship as a contractual bond between rulers and governed based on a preexisting system of legal rights which, if violated, justified revolt, was a feudal heritage. Writing in the context of the investiture controversy, the eleventh-century author Manegold of Lautenbach distinguished (as Knox essentially did later) between the office of the king, which was sacred, and an individual sovereign who could justly forfeit his authority. A king does this when he becomes a tyrant, that is, when he destroys justice, overthrows the peace, and breaks faith….

Thomas Aquinas opposed tyrannicide, but nevertheless favored active resistance against a tyrannical ruler, aimed at abolishing his tyranny in a manner that would not do more harm than the tyranny itself. Consequently, in a manner akin to Knox, Aquinas cautioned that “action against a tyrant should not be taken by the private presumption of individuals but rather by public authority.”

In his 2017 book Protestants, historian Alec Ryrie says this:

[Knox] had seen the future as a refugee in Geneva and wanted to make it work in Scotland. Above all, he was entranced by the idea of spiritual equality. In a series of polemics in 1558, he warned his fellow Scots that they could not shirk their responsibilities to reform the church simply because they were commoners. In God’s eyes, he insisted, “all men are equal”: equal not in rights but in responsibilities. If you lived in a land of idolatry, it was your duty to demand reform and to take action to separate yourself from the sin around you.

The words found in the opening pages of Steven Lawson’s brief 2014 biography of Knox are worth rounding out this article with:

John Knox was one of the most heroic leaders and towering figures in the annals of church history. Regarded as ‘the Father of the Scottish Reformation’ and ‘the Founder of the Scottish Protestant Church,’ Knox was a spiritual tour de force of unmatched vigor in spreading the kingdom of God. With resolute convictions, this fiery Reformer established his native land as an impenetrable fortress of biblical truth, one that would reverberate throughout the known world. If Martin Luther was the hammer of the Reformation and John Calvin the pen, John Knox was the trumpet.

Obviously much more can be said about both Knox and his views on resistance theory. But this piece, coupled with those already written, and more forthcoming, will help provide a platform for believers today as they wrestle with matters of church and state relations, how Christians should understand the role of government, and if there is ever a place for resistance to tyranny.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts