In 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) released the “Whose Heritage?” report on the Confederate symbols in the United States. This report had one thesis: The Confederate monuments, memorials, and namesakes were erected during the “Jim Crow” era to vindicate white supremacy without consideration of other factors. The report was based on undocumented sources, but the charting of monuments and namesakes was used to make the claim that the rise of Confederate monuments was attributed to “Jim Crow” racism. Thus, the fallacy was born, a fallacy that is easily refuted by even a cursory examination of readily available source material.

First, many Northern states had Jim Crow laws, with New York considered the Northern capital of Jim Crow. In fact, one can make a case—and many did—that Northern attitudes in regard to blacks were harsher than Southerners who had nearly a three-hundred-year history of race relations. Jim Crow and racism were not isolated to a single region.

Second, only looking at the Confederate monuments with a laser beam focus on “racism” ignores the history of monument construction across the United States, North and South. Northern communities had built 32 monuments by 1867 when the first Confederate monuments were erected in West Virginia and South Carolina.

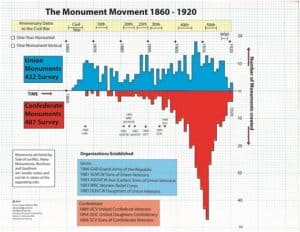

To get a better understanding of the Monument Movement, I conducted a study of the SPLC list of Confederate Monuments and created a corresponding list of Union Monuments utilizing a variety of internet, archival, and personal visits to the monuments. One variation is the Union list noted themes of the monuments which the SPLC did not consider. [The SPLC list 1,875 Confederate memorials of all types (physical, names, songs, license tags, etc.) was reduced to only monuments; there were 834 recorded. This list further reduced to end in 1920, leaving 487 physical monuments. The Union monument survey consisted of 700, which included buildings during the early survey work was reduced to 628 monuments, of which 422 were dated to before 1920. For the analysis, monuments without a date were removed though future research may date these to the period in question.] Eliminating non-monuments from the SPLC Confederate list and limiting the dates for work from 1860-1920, there were 487 Confederate Monuments. The list of Union Monuments, which is arguably incomplete but enough to draw some conclusions, contained roughly the same number, 422, and like the Confederate list and did not include Grand Army of the Republic memorial halls, streets names, and school namesakes.

During the War Between the States

The War Between the States was the first war where, in the aftermath, there was a movement to raise monuments to the local communities’ contributions to the war effort.

Monument to Confederate Col. Francis S. Bartow

The first monument, which was short-lived, was to Confederate Col. Francis S. Bartow of the 8th Georgia Infantry Regiment, where he was killed during the First Battle of Manassas (21 July 1861).[4] The “small pillar, in all respects like a milestone, has been erected on the spot where General Bartow fell” was built by September 1861. The Bartow monument was destroyed by the Battle of Second Manassas (29-30 August 1862), with the base as the only surviving reminder of the memorial.

An early effort for Union war monuments is to the 32nd Indiana is believed to be the oldest monument surviving to the memory of the war casualties. Private August Bloedner carved the memorial to mark 13 fallen members of the 32nd Indiana killed in the Battle of Rowlett’s Station in Munfordville, Kentucky on December 1861. In 2008, it was removed for conservation and is now on display at the Frazier History Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.

The earliest monument in situ is the Hazen Brigade Monument near Murfreesboro, Rutherford County, Tennessee named after Col. William B. Hazen of the 41st Ohio, who commanded a brigade. He held the line during the Battle of Murfreesboro in December 1862. The monument was built between June and October 1863.

Ladd and Whitney Memorial in Lowell, Middlesex County, Massachusetts

The earliest non-battlefield monument, and a first at a town hall, is the Ladd and Whitney Memorial in Lowell, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. It was dedicated on 17 June 1865 to PrivatesLuther Ladd and Addison Whitney, who joined Company D “Lowell Guards” 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. Upon arriving in Baltimore, Maryland, Ladd and Whitney were among the four soldiers and 12 civilians killed by a secessionist mob on 19 April 1861.

The North erected at least 11 monuments before 1866. Another ten monuments were documented in 1866 and 11 more in 1867. Thirty-two Union monuments stood by the time the first post-war Confederate monuments were erected in Romney, Hampshire County, West Virginia, and Chester, Chester County, South Carolina, in 1867.

Monumental Themes and Meanings

The survey noted the themes of the Union monuments based on the memorials’ wording. Monuments represent the loss of sailors and soldiers of the Union, with some elaborating the why. Common Union themes were Defenders of the Union (24), Died so the Nation Might Live (20), Preservation of the Union (16), and Preservation of the Constitution (4) sometimes in combination. Most of the monuments have a soldier, although variations include multiple soldiers and/or sailors, or Liberty in the form of a female classical goddess frequently holding a sword.

The only Union monument to date with a funerary theme is in Bristolville Monument (1863) in Trumbull, County Ohio, depicting a “funerary urn and decorated with crossed swords, cannon and rifles.” Another clearly mourning Union monument is the Soldiers and Sailors monument (1870) in Clark County, Ohio, where the soldier is portrayed as “Rest on Arms,” a command for Funeral Honors.

Unlike Northern monuments, funeral motifs are common in Confederate Monuments. The depiction of a log, cut stump, or a broken column is a funeral symbol for a life cut short. Many Confederate monuments have an upright stump or less often a horizontal log behind the soldier. The Talbot Boys Monument in Easton, Maryland, uses a broken wagon wheel at the soldier’s feet. It could be asked if this represents the life cut short of the Solider or the short life of the Confederacy thus leaving its meaning is open to interpretation.

A sheet over the stone is another “life cut short” or “burial” motif. A variation of this is the use of a Confederate battle flag, such as the Fort Sanders Monument in Knoxville, Knox County, Tennessee, and at the site of Camp Beauregard in Fulton County, Kentucky.

Confederate monuments are etched with their meanings. The Spartanburg, South Carolina Confederate Monument proclaims “teach our children’s children to honor the memory and the heroic deeds in the Southern soldier who fought for his rights granted to him under the Constitution” reflecting the South’s views that secession fulfilled the spirit of the United States Constitution.

Spartanburg, SC, Confederate War Monument, proclaims “Let this monument teach our children and our children’s children to honor the memory and the heroic deeds of the Southern Soldier, who fought for rights guaranteed him under the Constitution.”

Some monuments have a snippet of literature, typically part of a poem indicating mourning for the losses in the conflict. These snippets are frequently misunderstood when modern contexts are applied due to the assumed meaning and use of language from the 19th-century and the lack of a broader context of the words. Many contain a poem such as the Carroll County monument (1910) in Carrollton, Georgia which lists the words from Englishman William Collins’ 1746 poem “How Sleep the Brave.” The poem, written during the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), is about soldiers who made the supreme sacrifice for their county. The Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia monument (1878) uses a selection from a poem about Robert E. Lee by Philip Stanhope Worsley of Oxford, England. [William Bledsoe Philpott, editor, Sponsor Souvenir Album and History of the United Confederate Veterans’ Reunion 1895, (Houston, Texas: Sponsor Souvenir Company, 1985), p. 214.] One portion of this poem is the line “No nation rose so white and fair.” The references to “white and fair” in Worsley’s poem are better interpreted as pure and fair – such as to the ideas of the Constitution or the purity of the cause of independence. [Blevins, “Confederate Monuments are Community Memorials,” The Newnan (Georgia) Times-Herald, 28 September 2017, 4A.]

Most Confederate monuments simply state variations of “Our Confederate Dead” as the main memorial with some utilizing the idiom “Lest We Forget.”[17] The Confederate monuments, like the Union monuments, address the mourning and community loss, although the former also reflects on the loss of their young nation. (The debate about the Confederate States was an actual or legal nation is moot in the respect that Southerners who supported the Confederacy still felt it was their country, and this is occasionally reflected in wording on monuments.)

Union monuments often have a variation to the community dead generalizing along the theme of “those who gave lives from (name of the community).” Later monuments, erected by the Allied Orders, memorialized the loss of the Grand Army of the Republic Posts as veterans died off and posts closed.

No Confederate monuments appear to mention slavery. Although some interpret references to the Constitution and States’ Rights as implying slavery, this is a narrow interpretation of both as broader Constitutional interpretations and States’ Rights issues contributed to the causes of the war. Only three of 422 Union monuments (0.007%) mention slavery. Fredrick Douglass’ adopted hometown of New Bedford, Bristol County, Massachusetts monument notes possibly the earliest citing slavery as: “Erected by the Citizens of New Bedford in Tribute of Gratitude to her Sons who fell defending their Country in the Struggle with Slavery and Treason.” It is the only one to mention treason. The lack of Union monuments addressing slavery is an indication that few in the Union saw the conflict to end slavery.

The Grand Army of the Republic Monument (1880) in the Brookdale Cemetery in Dedham, Norfolk County, Massachusetts, makes a longer statement of the community’s sentiments. “Erected in 1880 as a monument to the loyal soldiers and sailors of Dedham, who served in the war of the rebellion 1861-1865. Many of whom died, and rest, in unknown graves and dying, broke the bondman’s chain and made the slave a man.” Dedham was the home of anti-slavery writer and abolitionist leader Edmund Quincy. Quincy supported the abolitionist movement since the 1830s.

The 1887 Lincoln, Penobscot County, Maine Monument cites “Preserved the Union/Destroy Slavery/Maintained Constitution.” This monument was paid for by Lincoln native Charles Stinchfield of Detroit, Michigan.

The community erected these monuments though ladies’ associations, monument associations, and veterans raised funds for the monuments. The Grand Army of the Republic (1866) was the first major veterans’ organization. By the early 1880s, the Union women and sons formed allied orders. The United Confederate Veterans was established in 1899 with the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans in the mid-1890s — meaning the Union monument movement had 36 years head start with organizational support to erect the memorials.

From 1867-1900 the Union erected an average of 6 monuments a year with the highest in that period in 1897 and 1899 with 13 each year. In the same time frame, 2.1 monuments a year with the highest year in eight in 1897. The Southern monuments numbers rose in the early 20th century preparing for the 40th and 50th anniversary years. Also, consider the veterans were dying off by these anniversaries, and efforts to honor them before passing was certainly part of the equation.

However, these same factors were occurring in the North, which memorialized earlier and more often. Thus, the spike of monuments is less significant in the anniversary years. It was not until 1914 did the Confederate monuments equal the Union monuments.

Monuments are Community Memorials

Soldiers monument on the Gervais Street side of the SC State Capitol. The monument states that the monument is to “perpetuate the memory” of those who “Found support and consolation in the belief that at home they would not be forgotten.”

What is clear about the Monument Movement is that it was a national movement. Union and Confederate monuments are community memorials. The communities came together in the time of war, contributing their men and boys (and a few documented women). Then they came together again to memorialize these soldiers and their contributions to the cause as they saw it. Citizens paid subscriptions to memorials, for monument associations, taxes were issued, the GAR, Allied Orders, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and the United Confederate Veterans all lead fundraisers.

Northern companies made Confederate and Union monuments crossing former lines of conflict for communities to memorialize their losses. As such, these resources are part of the cultural landscape, and should be regarded as the historical monuments.

Much of the research for decades only focused on the Confederate monuments and possible meanings. The same is lacking for the Union monuments. Union monuments’ resources are mostly lists and local history of the memorial containing no context to the larger historical picture. Further work is continuing to understand the Confederate and Union monuments; and how they fit into the national Monument Movement.

Ernest Blevins is a Structural Historian in Review & Compliance at the West Virginia State Historic Preservation Office and owns Blevins Historical Research. He also writes a regular history-oriented column for the Charleston (WV) Gazette-Mail. He researched and produced the video “Always Looking North”. He holds a BA in Studio Art, BS in Anthropology from the College of Charleston, MFA in Historic Preservation (Savannah College of Art & Design) and a Certificate in Public History (University of West Georgia). This article originally appeared in The Abbeville Blog.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts