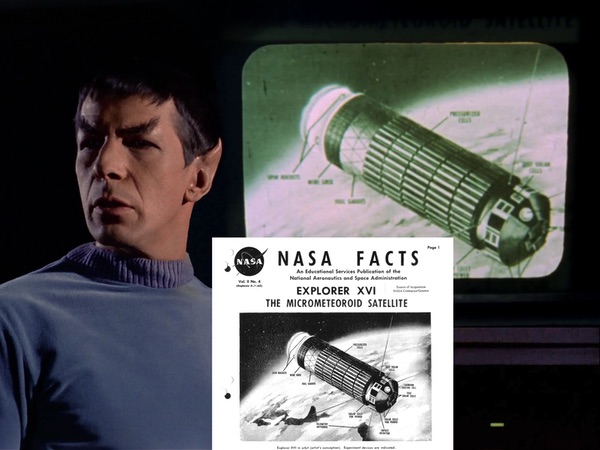

In the original Star Trek television series of the 1960s, creator Gene Roddenberry made use of NASA imagery and the growing national space rhetoric to help sell his show to network executives. (credit: CBS/Paramount/NASA)

These are the words of perhaps the most famous opening lines of narration in all of television history.

The introductory monologue by Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) invited viewers to join the crew of the starship Enterprise to watch a brand-new science fiction television series called Star Trek. Every week, households turned their television dial to NBC, where they witnessed series creator Gene Roddenberry’s vision of life in the 23rd century unfold in living color during the show’s initial three-year run that began on September 8, 1966.

A mid-century belief in the viability of space exploration saw a revitalization of the American frontier by those who sought to use the growing popularity of the nation’s space rhetoric to spread their message of exploration and conquest.

Those words that launched each opening episode were the result of a postwar popularization of space that was very much present at the time of Star Trek’s creation. A mid-century belief in the viability of space exploration saw a revitalization of the American frontier by those who sought to use the growing popularity of the nation’s space rhetoric to spread their message of exploration and conquest. This Cold War cultural effort to explore space reawakened a sense of manifest destiny in postwar America by reviving freedom, courage, and exceptionalism—the same ideals that originally drove expansionist boosters to America’s west. After all, how could a country that had tamed the great North American frontier by the end of the nineteenth century not succeed in conquering the frontier of space by the 23rd century?

By the mid to late 1950s, space became the realm in which writers sought to understand and portray the changes that were rapidly occurring all around them. Science fiction mushroomed as new pulp magazines emerged to address the growing popular interest. As a result of the growing aerospace industry, trade publications such as Missiles and Rockets and Aviation Week either adapted their original editorial content or were founded anew to cover the broad spectrum of space-related, scientific, and engineering culture that began to emerge in this new industrial field.

In the October 1956 premiere issue of Missile and Rockets, the publisher wrote, “This is the age of astronautics. This is the beginning of the unfolding of the era of space flight. This is to be the most revealing and the most fascinating age since man first inhabited the earth.”

In the midst of the Cold War, space started to become a real place in popular culture as both fiction and fact began riding on the back of a galloping technology and could not dismount for fear of breaking their necks. Together, they were on a convergent course, and the lines separating fact from fiction became more blurred. Nonfiction books that romanticized humanity’s future in the new frontier of space started to borrow the look and feel of many of the popular pulps.

This essay attempts to explore the origins of some of the national space rhetoric that appeared during the Cold War, the way its use in political documents, congressional reports and campaigns tells us something about the self-image of Americans in the early to mid 1960s, and how this rhetoric may have influenced Gene Roddenberry during the creation of his pioneering and highly influential television series Star Trek.

An ad appearing in the December 1957 issue of Fortune magazine illustrates the application of traditional western frontier rhetoric to that of space that occurred during the post-war period. (credit: Fortune magazine)

|

Have Phaser Will Travel

Frederick Jackson Turner claimed that the American frontier had shaped America and defined the characteristics of being American. Turner was an American historian who espoused a view on how the idea of the frontier shaped American being and culture. Known as the “Frontier Thesis,” Turner posited that it was the idea of the Western Frontier that drove American history and, as a result, explained why America is what it is. The frontier facilitated a certain rugged individualism in those who explored it. In this manner, Turner argued, the story of this continual westward push “with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive society, furnished the forces dominating American character.”

Turner’s seminal essay outlining his thesis was first presented at a special meeting of the American Historical Association at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and published later that same year. Well regarded for many years, Turner’s framing of American history began to be challenged starting in the early 1940s.

At the same time that some people lamented what they considered the closing of the American Western frontier, some Americans searched for a “new” or “final” frontier, both in popular rhetoric and in culture.

At the same time that some people lamented what they considered the closing of the American Western frontier, some Americans searched for a “new” or “final” frontier, both in popular rhetoric and in culture. By the middle of the twentieth century, many Americans found it through television. Star Trek was heavily influenced by these discussions of a new frontier, particularly the language that politicians and government officials applied to space flight. Even though Turner’s thesis has largely been rejected by later historians, the myth of the Western Frontier still held a powerful grip on American consciousness, and books, movies, and eventually television shows about the West became wildly popular in the twentieth century. After all, the story of the settling of the American West is, according to Turner, that of how Americans came into their own unique character. “The frontier,” Turner explains, “is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization.”

The evolution of Frontier-themed advertising. A movie poster from the 1935 Western The New Frontier starring John Wayne. A 1962 Red Ball Jets brand shoes promotional space item. (credit: Republic Pictures and Red Ball Shoes)

|

As television became more popular by the late 1950s, the main genre was Westerns. By 1959, 30 Westerns aired on prime time each week. One of the hundreds of writers for TV Westerns openly wondered, “I don’t get it. Why do people want to spend so much time staring at the wrong end of a horse?”

At the same time that Clayton Moore, who played the title role in television’s popular The Lone Ranger, was rescuing folks tied across rails as steam engines came barreling down toward their protagonist’s certain doom, a new railroad to the stars began to emerge. The Western as a genre held such a prominent place in America’s culture because it provided a reliable formula for filmmakers to explore American history and character. Westerns would still remain popular as a television mainstay into the 1960s, but a new frontier was beginning to attract people’s attention, heralded by a young senator from Boston.

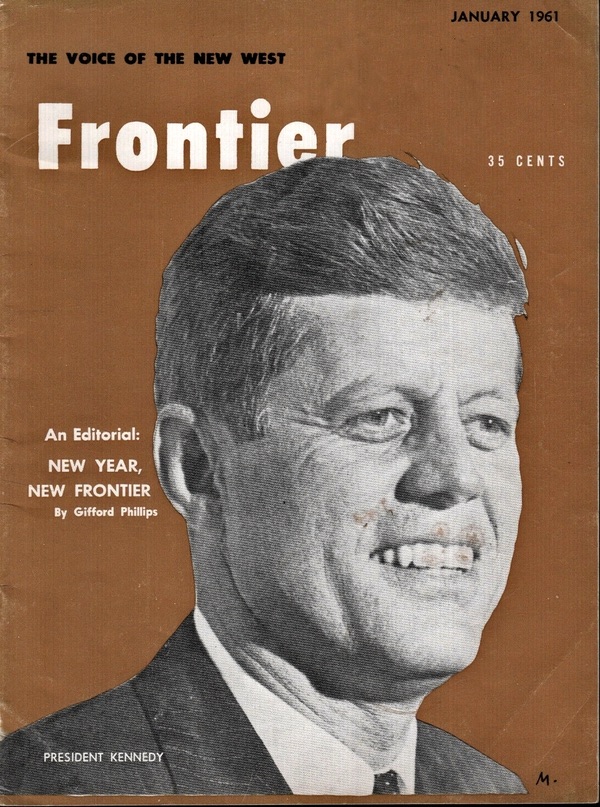

The monthly magazine Frontier: The Voice of the New West, published from 1949 to 1967, advocated progressive and liberal views as it covered local, national, and international issues. (credit: Frontier magazine)

|

Kennedy and the New Frontier of space

The term “new frontier” was first used by John F. Kennedy during the 1960 Democratic National Convention. In giving his acceptance speech as his party’s presidential nominee at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on July 15, Kennedy said, “We stand today on the edge of a New Frontier—the frontier of the 1960s, the frontier of unknown opportunities and perils, the frontier of unfilled hopes and unfilled threats… Beyond that frontier are uncharted areas of science and space.” During his presidency, the phrase became a label for his administration’s domestic and foreign policies both on Earth and off.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, President Kennedy exploited a growing public concern about the space race that was fueled by an insistence that there was a “missile gap,” an illusion that his party put forth at the expense of the Eisenhower Administration. This feeling of technological inadequacy was further enhanced by a series of successive space spectaculars performed by the Soviet Union that, when compared to several early American launch failures, created a public fear that the United States had indeed fallen behind their Russian counterparts in the production of ballistic missiles.

In the October 10, 1960, issue of Missile and Rockets, one of the prominent trade journals that emerged in the rapidly growing field of aerospace, Kennedy issued a campaign statement on space: “We are in a strategic space race with the Russians, and we are losing… Control of space will be decided in the next decade. If the Soviets control space they can control Earth, as in past centuries the nation that controlled the seas has dominated the continents. This does not mean that the United States desires more rights in space than any other nation. But we cannot run second in this vital race. To insure peace and freedom, we must be first… This is the new age of exploration; space is our great New Frontier.”

For those who lamented the end of the frontier, there now emerged the new frontier of space that allowed fearlessness, rugged individualism, and other American qualities to re-emerge in the face of imminent danger posed by the Soviet Union.

After the completion of his 1962 Mercury flight in which he became the first American to orbit the Earth, Glenn left NASA to pursue a highly successful career in politics. (credit: G. Swanson)

|

On May 25, 1961, less than three weeks after astronaut Alan Shepard safely splashed down in his Mercury spacecraft marking the first time an American had flown into space, President Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress where he outlined an audacious plan to raise America’s eyes to the stars and land men on the Moon.

Throughout Kennedy’s 22-page speech, he uses the word “space” 17 times, and all but three of those occurrences appear on the last six pages where he described space as the “new frontier” before launching into his manned lunar landing goal.

Roddenberry sought to employ some of the public enthusiasm generated by Kennedy’s support for human spaceflight to help launch a new science fiction show that he had been developing.

Seizing on the popular interest generated by the President’s speech, NASA issued a publication that helped explain to the public what the less-than-five-year-old federal space agency planned to do to realize the national goal of achieving a manned lunar landing before the end of the 1960s.“Finally, if we are to win the battle for men’s minds,” said Kennedy, “the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all the impact of this new frontier of human adventure…I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more exciting, or more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

The result was SPACE The New Frontier, a heavily illustrated 50-page publication that proved so popular when it first appeared in 1962 that NASA published it multiple times over the next four years.

Among those studying this new document was Gene Roddenberry.

Cover of a popular NASA publication first released in 1962. Gene Roddenberry used images from this in the first Star Trek pilot “The Cage.” The NASA publication proved so popular that it was re-printed in subsequent editions over the next four years. (credit: NASA)

|

NASA and Gene Roddenberry’s “Wagon Train to the Stars”

Roddenberry had been a World War II bomber pilot, a commercial airline pilot, and a police officer before turning to television writing by the 1960s. Although not a science fiction fan, he recognized that the genre could be used to shed light on social problems that might be too sensitive when addressed in other television genres.

Roddenberry sought to employ some of the public enthusiasm generated by Kennedy’s support for human spaceflight to help launch a new science fiction show that he had been developing.

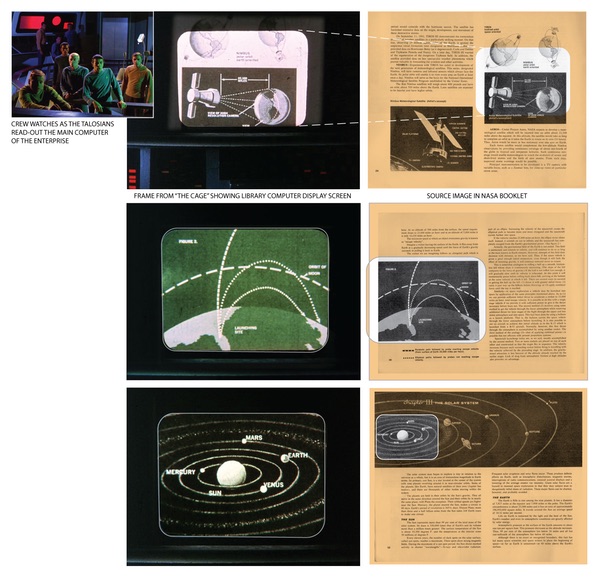

In 1964, Roddenberry began filming “The Cage,” the pilot for a proposed new television series called Star Trek. Pitched to network executives as a “Wagon Train to the stars”—a reference to a popular episodic television Western—it offered a natural extension to President Kennedy’s “New Frontier” rhetoric and also relied heavily upon NASA for inspiration and even imagery.

In the pilot, the crew of the Enterprise receives a distress call from the fourth planet in the Talos star system. After beaming down to the planet’s surface, the landing party discovers survivors from an expedition who had been missing for eighteen years. Among the survivors is a beautiful young woman named Vina who manages to lure Captain Christopher Pike into a trap. After being captured, it turns out that everything except for Vina are just illusions created by the Talosians, a race of humanoids with giant pulsating heads and powerful telepathic abilities who live beneath the planet’s barren surface. During Pike’s imprisonment, he learns that the Talosians seek to repopulate their decimated planet using himself and Vina as breeding stock to create a race of slaves, as well as psychologically entertain themselves. The crew of the Enterprise tries to rescue the captain, and during this time, the Talosians glean records from the Enterprise’s computer banks which, among other things, show how much the human race despises captivity. With this new knowledge, the Talosians eventually let the Captain and the rest of his crew go, but Vina remains as it is learned that she cannot leave the planet. Vina was the sole survivor of the expedition, but was badly injured when they crashed on the surface. The Talosians were able to save her but she was badly “broken.” Because they had no knowledge about human physiology, they had no idea how to put her back together again, and as a result, she was horribly disfigured. The episode closes with the Talosians showing Vina to the departing crew as an illusion of perfect health and beauty with telepathically created Captain Pike by her side.

During the sequence when the Talosians are going through the Enterprise’s computer records, multiple images flash across one of the bridge view screens. It turns out that many of these images were taken from original NASA documents that were seen and approved by Roddenberry.

Scenes from Star Trek’s first pilot “The Cage” featured numerous images from various NASA publications, including these. (credit: CBS/Paramount/NASA)

|

Housed in the special collections at UCLA are the Roddenberry Papers, an immense resource that allows scholars to learn more about Star Trek and the man who was instrumental in its creation. Included are documents describing how Roddenberry oversaw every detail of the development of his series, and which show its numerous ties to the American space program.

In a memo dated November 23, 1964, when “The Cage” was in postproduction, Roddenberry sought ideas for images to show in the scene where the Talosians are “extracting” information from the U.S.S. Enterprise. In a follow-up memo issued to Darrell Anderson, who filmed the special visual effects, Roddenberry gives a detailed annotated list of NASA documents, pamphlets, and papers complete with instructions on what pages to be filmed for the “Subliminal, Knowledge Montage” sequence. Of the 19 confirmed NASA images that appear in this “slide show” nearly half of them come from one single NASA publication: SPACE The New Frontier.

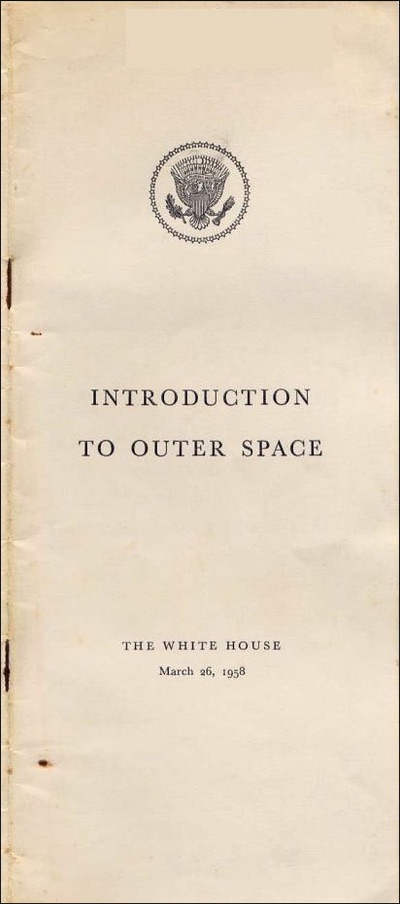

The cover from the pamphlet Introduction to Outer Space issued by the Eisenhower Administration in 1958 to help educate the general public on space and “to go where no one has gone before.” (credit: US Government Printing Office)

|

Eisenhower and “Where No One Has Gone Before”

The influence of America’s space program on Star Trek went beyond simply providing imagery for episodes. There is also evidence that other aspects of Star Trek were inspired, directly or indirectly, by the way Americans were talking about space in the first half of the 1960s. There is even reason to believe that the first line of Kirk’s memorable opening speech to each Star Trek episode was influenced by President Kennedy’s New Frontier rhetoric and reinforced by a NASA publication emblazoned with the same words. If true, this would not be the first time that the origins of Star Trek’s famous opening narration may have been attributed to the US government.

A White House document produced during the Eisenhower Administration included the following: “…the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.”

In a 2005 article in this publication, spaceflight historian Dwayne Day suggested that the final line of Star Trek’s beginning narration “to boldly go where no man has gone before” may have been inspired by another 1958 document. In 1958, the Senate formed a Special Committee on Space Technology and issued a document titled Recommendations to the NASA Regarding A National Civil Space Program. In this report, the nation’s civil space research program’s mission is “to explore, study and conquer the newly accessible realm beyond the atmosphere,” a somewhat similar goal to that of the starship Enterprise’s mission to “explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations” (well, maybe all but the “conquer” part.)

A White House document produced during the Eisenhower Administration included the following: “…the compelling urge of man to explore and to discover, the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.”

Though not exactly the same as Kirk’s “to boldly go where no man has gone before,” President Eisenhower’s original wording was picked up years later when Roddenberry used the gender neutral “where no one has gone before” for Captain Jean-Luc Picard’s (Patrick Stewart’s) opening narrative of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

In the wake of the national concern brought on by the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik 1 in late 1957, Dr. James R. Killian, chairman of the newly created Presidential Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), produced Introduction to Outer Space. The document was created to help explain the new concept of spaceflight “for the nontechnical reader” and to help generate support for Eisenhower’s new national space program.

The document proved so well liked by Eisenhower that he ordered it made available to everybody. As a result, in 1958 thousands of copies of Introduction to Outer Space were produced in pamphlet form and sold by the Superintendent of Documents Government Printing Office for 15 cents each.

In the preface, Eisenhower explained that the study of space “is not science fiction. This is a sober, realistic presentation prepared by leading scientists. I have found this statement so informative and interesting that I wish to share it with all the people of America and indeed with all the people of the Earth. I hope that it can be widely disseminated by all news media for it clarifies many aspects of space and space technology in a way which can be helpful to all people as the United States proceeds with its peaceful program in space science and exploration.”

Eisenhower closes with this: “This statement of the Science Advisory Committee makes it clear the opportunities which a developing space technology can provide to extend man’s knowledge of the Earth, the solar system, and the universe. These opportunities reinforce my conviction that we and other nations have a great responsibility to promote the peaceful use of space and to utilize the new knowledge obtainable from space science and technology for the benefit of all mankind.”

Noticeably absent in Killian’s document is an emphasis on the role of humans in space. The pamphlet stresses the “remotely controlled scientific expedition to the moon and nearby planets” arguing that such efforts “could absorb the energies of scientists for many decades.” Eisenhower’s vision for space relied heavily upon robotic satellite technology and downplayed the role of human spaceflight.

By 1965, Kapell concludes, “NASA had fully accepted the mythic frontier underpinnings of their overall project, proclaiming that its missions were ‘exploration in the truest and most romantic sense’ and that space was, therefore, ‘the most recent of these ‘last’ frontiers’ of such exploration.”

Similar occurrences of lines from Star Trek’s opening narration appear in earlier literature. Famed 18th century British explorer Captain James Cook during an expedition aboard the Resolution in search of “The Great Southern Land” of Australia declared on January 30, 1774, that, “ambition leads me not only farther than any man has been before me, but as far as I think it is possible for a man to go.”

Whether Roddenberry directly borrowed language from any of these sources to form Star Trek’s famous opening lines of narration is not known for certain. However, what is known for sure is that Roddenberry had access to these and a whole lot more.

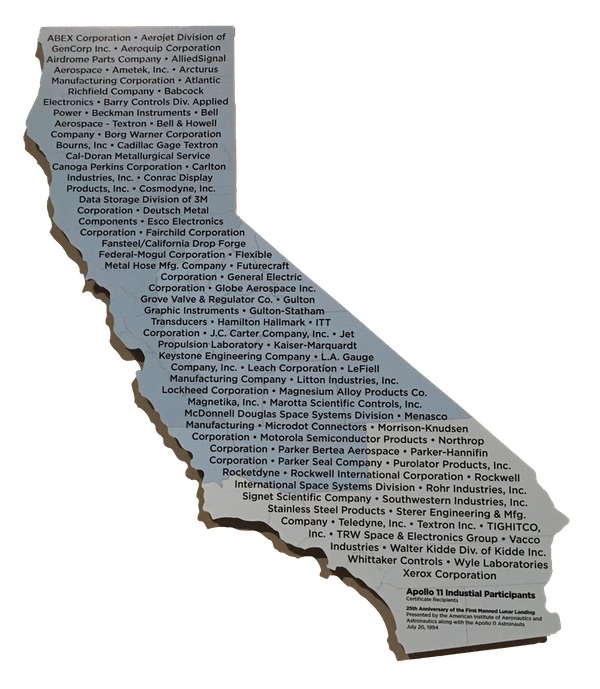

Presented by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics during the 25th Anniversary of Apollo 11, this plaque lists the many aerospace industries present in California during the time of Apollo. (credit: Photo taken by G. Swanson during the Apollo 11: One Giant Leap for Mankind exhibit at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum)

|

By the end of World War II, 60–70% of the American aerospace industry was situated in Southern California. When Roddenberry began developing Star Trek, the Cold War was at its peak and 15 of the 25 largest aerospace companies in the United States were based in Southern California. There was so much space activity going on in the region that, by the early 1960s, NASA established a Western Operation Office in Santa Monica. Leaving the film and television studios in and around the greater Los Angeles area, Roddenberry did not have to travel very far to find inspiration. With so much “space stuff” readily available, it is not at all surprising that he would have made use of some of it for his show.

The invention of space as the final frontier

In the years since the original series went off the air, Star Trek became one of the most studied science fiction shows ever produced. There are a great number of serious academic studies that explore the influences and cultural impacts of the new frontier of space and Star Trek’s role in it.

A good example is Matthew Wilhelm Kapell’s Exploring the Next Frontier: Vietnam, NASA, Star Trek and Utopia in 1960s and 1970s American Myth and History (Routledge, 2015). Kapell argues that the national space rhetoric that emerged from Congress, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and NASA has largely been viewed through “a prism of Cold War politics.” Kapell posits that the post Cold-War declassification of documents has shifted the geopolitical reasoning for the Space Race from the traditional overly simplistic goal of establishing technological preeminence over rival nations to something more complex.

Kapell argues that examining a Cold War Space Race is not the only way to look at the period. He notes that national space rhetoric, particularly that dealing with the frontier, had been part of the NASA institutional culture and its public face since the beginning of its formation. He points out that congressional hearings in 1960 accepted that “we yield to the urge to explore that is an American heritage.” By 1965, Kapell concludes, “NASA had fully accepted the mythic frontier underpinnings of their overall project, proclaiming that its missions were ‘exploration in the truest and most romantic sense’ and that space was, therefore, ‘the most recent of these ‘last’ frontiers’ of such exploration.”

In Destined for the Stars: Faith, Future, and America’s Final Frontier (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019) historian Catherine Newell explores the idea of how humanity first got the idea that outer space is a frontier waiting to be explored. She argues that the foundation of the conquest of space is above all a religious endeavor and that “the space race didn’t inspire America’s imagination as much as it was inspired by America’s collective imagination.”

From European settlers in America seeking to explore the nineteenth century western frontier beyond the Ohio River Valley to mid-century Americans eyeing the frontier of the heavens, Newell argues that this is a story “that has little to do with the political mechanizations and Cold War strife we associate with the history of the space race and everything to do with the invention of space as a frontier.”

Newell notes that from the end of the Second World War to the beginning of the Cold War, exploring the outer planets was a “spiritual necessity” that resulted from our need “to escape the inevitable cataclysm that would befall Earth.” Newell contends that the exploration of space was not borne merely as a result of technological or economic superiority or by a national effort motivated by political and ideological fears. Rather, the success of the US space program was due to “a culture that had long valued faith above other religious feeling and believed they were called by God to settle the new frontiers and to prepare for the end of time.”

The traditional historical narrative of the space race is that it was the culmination of a great leap forward in technology and scientific knowledge driven by a fear that the Soviet Union was ahead of the US and that, as a result, America was in a “space race.” Newell argues that this version of events is oversimplified and ignores two important elements. One is that the popularization of space exploration after the Second World War had its genesis well before the Soviet Union’s space program became an acknowledged threat. The second is that the popularization drew heavily on Americans’ religious beliefs from the previous century.

Newell posits that the success of the US space program was not just the result of technological superiority but rather by a culture that held a long tradition of believing that they were called by God to settle new frontiers. The move West, which began with a fear that the end of the world was coming and that the New World needed to be purified of the sins of the Old, led to the conquest of the frontier. By extension, this was then interpreted as a divine sign that God had a hand in the lives of His chosen people. All of this mapped perfectly toward a future in space. How could a country that had tamed the great West not succeed in conquering the final frontier?

Newell does not disavow the role that technology and science played in the exploration of space. Indeed, she notes that it was because of our demonstrated ability to solve the many problems associated with physically going into space and back that space exploration “could finally become an object of American belief and an endeavor Americans could say they truly had faith in.”

Holmes argued that if mankind could avoid blowing itself up in a nuclear war that “when it becomes technically feasible, men will explore the planets, the stars and even other galaxies.”

Other scholars argue that Star Trek appeals to western democracies by its ability to maintain a western theme through the show’s reinvention of the frontier spirit as it celebrates the space cowboy. Prior to creating the series, Roddenberry had written a number of episodes for such television series as Boots and Saddles, Whiplash, and Have Gun Will Travel and even produced Wrangler, a short-lived western that aired on NBC, so it is not at all a surprising that such frontier themes would find their way into the stars through Star Trek. Upon reading Star Trek’s opening lines of narration, others interpret them as being less noble in their origins. Scholar Valerie Fulton suggests that Roddenberry’s wording is nothing other than classic imperialism. In her paper “Another Frontier: Voyaging West with Mark Twain and Star Trek’s Imperialist Subject,” she notes that the show’s governing body, known as the “Federation,” has as its goals to both “seek out new life and new civilizations” and “to boldly go where no man has gone before.” Fulton argues that these two missions clearly contradict each other unless read through the lens of frontier ideology which grants new civilizations existence only to the extent that the original culture has ‘found’ them.

Keep on Trekkin’

In a little over 20 years since the end of the Second World War, the dream of space exploration emerged from the pages of science fiction to become first a government policy by the Eisenhower Administration who formed NASA that got America into space, then as political rhetoric used by John F. Kennedy to help propel him to the presidency and take us to the Moon.

In a 1962 book about NASA’s newly formed Apollo Program, fittingly subtitled The Enterprise of the 60s, author Jay Holmes presented an aura of inevitability and historical necessity for the lunar landing missions. Holmes argued that if mankind could avoid blowing itself up in a nuclear war that “when it becomes technically feasible, men will explore the planets, the stars and even other galaxies.” Henry S.F. Cooper, Jr., writing just months before the landing of Apollo 11, was more blunt: “man’s destiny must somehow be worked out among the stars.” Cooper went on to write that of those that worked for NASA “[this] notion may be part of what keeps them all going.”

When Star Trek first premiered in 1966, it was during a time when America was falling apart. The war in Vietnam began to further escalate while civil unrest continued at home. But interest in space exploration was still popular in American culture as Roddenberry’s new “Wagon Train to the stars” sought to invoke the same frontier nostalgia as seen in the many popular Westerns that competed for television viewers every week. Like the American frontier that allowed a belief in rugged individualism during the nineteenth century, Star Trek allowed Americans to believe that the new frontier of space exploration represented a better tomorrow. This optimism was one of the key factors in the show’s later popularity.

“When Star Trek was first on the air in its network run, we were just getting into space. When we made our first episode, we hadn’t even been to the moon; only toward the end did people begin to accept space,”[29] said Gene Roddenberry upon reflecting back on the success of his television series. “Star Trek came along and said, ‘Hey, we made it!’ It’s a program that said there is basic intelligence and goodness and decency in the human animal that will triumph over these things.”

A little more than six weeks after the last episode of Star Trek aired, Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade became a reality when the crew of Apollo 11 stepped out onto the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. At the same time that millions of people across the globe saw fuzzy black and white images of Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong walk across the moon, others continued to hear William Shatner’s famous lines of opening narration. Prior to the airing of the last Star Trek episode on June 3, the series had been sold into syndication to Kaiser Broadcasting, which owned a small chain of local television stations along the East and West coasts. Kaiser continued to broadcast the series and saw a steep rise in viewership as a result. Others took note and began queuing up to carry the series as well. As a result, Star Trek was picked up by other stations across the country, becoming one of the most heavily syndicated shows in the history of television and creating legions of new fans who continue to “boldly go where no man has gone before.”

Please “like”, comment, share with a friend, and donate to support The Standard on this page.

Independent journalism is critical at this time in our country when it seems the left has taken over the dominant media. When you support The Standard, you support independent media and freedom of the press at a time when all our Liberties are under attack! Join us now and support freedom of the press for as little as $1 a month! Would you click the donation button now?

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts