The Magnificent Seven (1960). Photo courtesy Cleveland.com and United Artists.

Hollywood has a clever way of distorting our perspective on history, and a great example of this is Western film – a movie genre we’ve all come to love. Cattle rustlers, guns blazing, outlaws running loose, and vigilantes dishing out vengeance indiscriminately. These scenes have become more synonymous with the American Frontier than Winchester and their “Cartridge That Won the West.” But these fictional tales have produced more than entertainment for over a century; they’ve also contributed to an ongoing, subtle push for gun control, all while making Hollywood millions.

Revisionist history books tell us that the “Wild West” was an anarchic period of time that was not conducive to human prosperity. Images of a Hobbesian nightmare – a life that is brutish and short – are ingrained in our consciousness thanks to decades of public schooling and violent images on the silver screen which are light on actual history and heavy on creative license.

However, individuals who believe in liberty and developing their critical thinking faculties should be skeptical of most mainstream narratives regarding history, especially American history. After all, these narratives by and large have been created by Hollywood, a legacy institution that has historically advanced politically correct content with the support of Washington in order to perpetuate the cultural status quo.

When the curtain of political correctness that’s been draped over this particular period of history is pulled back, we see a much more nuanced picture of the American Frontier. In fact, research by historians such as Peter J. Hill, Richard Shenkman, Roger D. McGrath, Terry Anderson, and W. Eugene Holland shows that this period was rather indicative of a “not so wild, Wild West.”

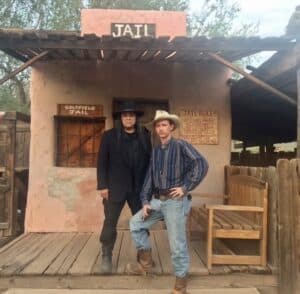

Cowboy Daniel Reed portrays the old west lawman in the street of Tombstone, Arizona.

For the purposes of this article, the Wild West will now be referred to as the Old West. This is by no means a pedantic distinction, but rather an acknowledgment of the fact that this time period was not “wild” by any stretch of the imagination when compared to other chaotic periods in human history. Indeed, the Old West had its fair share of challenges for American settlers. But as we’ll see below, crafty settlers found ways through ingenuity and mutual cooperation – all done with very limited state interference – to create a stable order for generations to come.

So let us delve into the “not so wild, Wild West.”

The Not-So-Violent West

Daniel Reed and Geronimo Lightfoot stand outside Tombstone, Arizona jail. Hollywood often misrepresents the old west as the ‘wild west’ thus pushing gun control.

The Old West was not a paradise by any stretch of the imagination. There existed conflict between groups, such as American settlers and Native American tribes, once they came in contact in the Great Plains and other parts of the frontier. This was natural due to the cultural differences that existed between these groups and the lack of defined property rights in those regions.

However, in more settled towns on the frontier, there was not as much violence as the Hollywood flicks would like you to believe. One of the most important texts disrupting this depiction of the Old West was W. Eugene Hollon’s Frontier Violence: Another Look. Hollon argued that “the Western frontier was a far more civilized, more peaceful, and safer place than American society is today.” Additionally, historian Richard Shenkman makes the case that the popular depictions of the Old West belong more in a movie script rather than a real-life historical account.

Shenkman noted:

“Many more people have died in Hollywood Westerns than ever died on the real Frontier.”

Dodge City (1939) with Errol Flynn

Dodge City has become a landmark for Western movies, but its portrayal is more fiction than reality. Shenkman also dismantled the Dodge City myth:

“In the real Dodge City, for example, there were just five killings in 1878, the most homicidal year in the little town’s Frontier history: scarcely enough to sustain a typical two-hour movie.”

Larry Schweikart of the University of Dayton also pointed out that the infamous bank robberies that captivate movie audiences were not very frequent. His research uncovered that there were fewer than a dozen bank robberies in the frontier West from 1859 to 1900. In essence, Schweikart argues that there are “more bank robberies in modern-day Dayton, Ohio, in a year than there were in the entire Old West in a decade, perhaps in the entire frontier period.”

Related Podcast

Arguably, the strongest and most concise text reclaiming the true history of the American West, Terry L. Anderson and Peter J Hill’s The Not So Wild, Wild West has forever changed the way Americans view the American Frontier. Anderson and Hill’s research found that the establishment of property rights was key in taming the American West. Indeed, this process took time, but it was well worth it. The Old West was a demonstration of human ingenuity and long-term planning that eschewed the quick fixes of modern-day politics.

In mining-related matters, American settlers found ways to peacefully adjudicate disputes, which Anderson and Hill noted:

“In the absence of formal government, miners in a particular location would gather and hammer out rules for peacefully establishing claims and resolving disputes over them.”

The authors went as far as to say that the “rules that govern western mining and mineral rights evolved literally from the ground up.” These developments in the Old West were no trivial occurrences, they set the stage for even bigger developments that the authors note below:

“Not only did the miners pave the way for mineral rights throughout the West, but they laid the foundation for western water law.”

This manner of peacefully settling property rights disputes carried over into other sectors, such as ranching and farming. There were obviously various roadblocks at the start, but settlers still found free-market ways of getting around these obstacles. In sum, Anderson and Hill’s findings demonstrated that the Old West was not so chaotic:

“In the mining camps and on the open range, the six-gun seldom served as the arbiter of disputes. Instead, miners established rules in camp meetings, and cattlemen used their associations to carve up the range, round up their cattle, and enforce brand registration. Though not all attempts at dispute resolution succeeded, institutional entrepreneurs found ways to define and enforce property rights that created, rather than destroyed, wealth. In short, the West was really not so wild.”

Such scenes of mutual cooperation on a voluntary basis are almost unheard of in today’s political climate. For many busybody politicians, all meaningful economic activity must be conducted under government supervision. As a matter of fact, had any of the problems in the Old West surfaced in present times, there would be instant calls for the government to step in and try to fix things. Once the unintended consequences of these interventions set in, the same calls for more government “help” would come back to life.

Thankfully, our forebears were much wiser in the late 19th century. By maintaining a relatively hands-off approach, the federal government allowed the unsettled American Frontier to naturally tame itself through the voluntary cooperation of settlers.

Understanding Violence in the American West

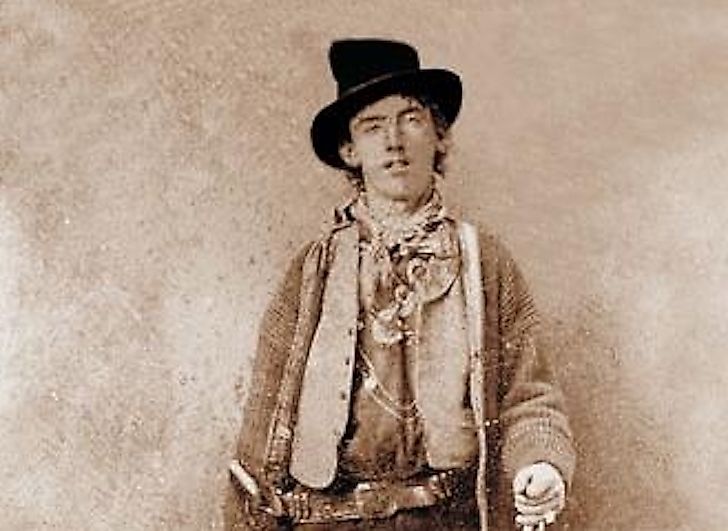

Billy the Kid in 1881.

The most infamous images of the American West always consist of scenes of extreme violence and vigilante justice. Many history books have implanted in the minds of millions of students that gratuitous violence was a normal way of life in the American Frontier. It also does not help that Hollywood’s greatest Western films were laden with epic shootouts and cliche conflicts between outlaws and law enforcement.

Although there are some slivers of truth in these depictions of the American West, they tend to be exaggerated. Since the 1970s, a wide array of literature has challenged these common assumptions.

In Gunfighters, Highwaymen, and Vigilantes, historian Roger McGrath looked at notable western cities in California, Bodie and Aurora, to see how they stacked up to modern cities as far as crime rates were concerned. McGrath provided some context to famous scenes of bank robberies in the Old West:

“Next to stagecoach robbery, bank robbery is probably the form of robbery most popularly associated with the frontier West. Yet, although Aurora and Bodie together boasted several banks, no bank robbery was ever attempted. Most of the bankers were armed, as were their employees, and a robber would have run a considerable risk of being killed.”

Armed citizens also deterred the robbery of individuals, while armed homeowners and merchants discouraged the burglary of homes and businesses. So it’s clear America’s long established gun culture and civic responsibility of providing defense transitioned quite seamlessly to the American frontier.

McGrath provided some interesting statistics on robberies in Aurora and Bodie:

“Between 1877 and 1883, there were only 32 burglaries – 17 of homes and 15 of businesses – in Bodie. Again, Aurora seems to have had fewer still. At least a half dozen attempted burglaries in Bodie were thwarted by the presence of armed citizens.”

The historian then compares these numbers to American cities:

“Bodie’s five-year total of 32 burglaries converts to an average of 6.4 burglaries a year and gives the town a burglary rate of 128 on the FBI scale. In 1980 Miami had a burglary rate of 3,282, New York 2,661, Los Angeles 2,602, San Francisco-Oakland 2,267, Atlanta 2,210 and Chicago 1,241. The Grand Forks, North Dakota, rate of 566, and the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, rate of 587 were lowest among U.S. cities. The rate for the United States as a whole was 1,668, or thirteen times that for Bodie.”

Even general theft was not much of a problem in cities like Bodie:

“Bodie’s forty-five instances of theft give it a theft rate of 180. In 1980 Miami had a theft rate of 5,452, San Francisco-Oakland 4,571, Atlanta 3,947, Los Angeles 3,372, New York 3,369, and Chicago 3,206. Lowest theft rates among U.S. cities were those of Steubenville, Ohio, at 916, and Johnstown, Pennsylvania, at 972. The rate for the United States as a whole was 3,156, more than seventeen times that for Bodie.”

McGrath came to several powerful conclusions when observing Aurora and Bodie’s robbery rates:

“Institutions of law enforcement and justice certainly were not responsible for the low rates of robbery, burglary, and theft. Rarely were any of the perpetrators of these types of crime arrested, and even less often were they convicted.”

In McGrath’s view, armed citizens were the key factor behind low burglary rates:

“The citizens themselves, armed with various types of firearms and willing to kill to protect their persons or property, were evidently the most important deterrent to larcenous crime.”

Gun Duel

This is consistent with findings that gun researcher John Lott uncovered in More Guns Less Crime when he analyzed states that liberalized gun laws during the 1980s and 1990s. Many of these states witnessed substantial decreases in robberies when citizens were allowed to not only defend their homes, but also carry firearms for self defense.

As far as rape was concerned, women were virtually safe from all occurrences of rape in Aurora and Bodie:

“Aurora’s and Bodie’s records of no rapes and thus rape rates of zero were not matched by nineteenth-century Boston or Salem. From 1880 through 1882, Boston had a rape arrest rate of 3.0 and Salem 4.8. A conversion factor of 2.6 – a figure consistent with FBI data in 1980 – gives the towns rape rates of 7.8 and 12.5. Nor are Aurora’s and Bodie’s rates matched by any U.S. city today, although in 1980 Johnsontown, Pennsylvania, had a rate of only 5.7.”

McGrath did concede that homicide rates were indeed high in the Old West, but there was a caveat – these cases of homicide were confined to fights between willing combatants, i.e., duels, as was common during this period where “honor culture” prevailed.

McGrath explained:

“While the carrying of guns probably reduced the incidence of robbery, burglary, and theft, it undoubtedly increased the number of homicides. Although a couple of homicides resulted from beatings and a few from stabbings, the great majority resulted from shootings.”

When we think about it, this makes sense. Firearms are very effective tools in dishing out legal damage. Guns did facilitate homicides, but McGrath argued that there was some nuance to this:

“The citizens of Aurora and Bodie were generally not troubled by the great number of killings, nor were they very upset because only one man was ever convicted by the courts of murder or manslaughter. They accepted the killings and the lack of convictions because those killed, with only a few exceptions, had been willing combatants, and many of them were roughs or badmen. The old, the weak, the female, the innocent, and those unwilling to fight were rarely the targets of attacks. But when they were attacked – murdered – the reaction of the citizens was immediate and came in the form of vigilantism.”

Even in a relatively anarchic environment like the American Frontier, there was a tendency for society to police itself in some shape or form. When the weak were attacked, citizens in these towns responded in vigilante fashion, but McGrath showed it was not as chaotic as people think:

“Contrary to the popular image of vigilantes as an angry, unruly mob, the vigilantes in both Aurora and Bodie displayed military-like organization and discipline and went about their work in a quiet, orderly, and deliberate manner.”

All in all, McGrath concluded that the violence we see in major urban centers today bears very little resemblance to violence in the American West:

“The violence and lawlessness that visited the trans-Sierra frontier most frequently and affected it most deeply, then, took special forms: warfare between Indians and whites, stagecoach robbery, vigilantism, and gunfights. These activities bear little or no relation to the violence and lawlessness that pervade American society today. Serious juvenile offenses, crimes against the elderly and weak, rape, robbery, burglary, and theft were either nonexistent or of little significance on the trans-Sierra frontier. If the trans-Sierra frontier was at all representative of frontiers in general, then there seems to be little justification for blaming contemporary American violence and lawlessness on a frontier heritage.”

Because of nearly a century’s worth of historical misinformation spread in popular culture and schools, Americans have been led to believe that the American Frontier was the violent period in American history. On the other hand, progressive urban centers like Chicago and Washington, D.C. are held up as enlightened cosmopolitan hubs, when in fact, they have witnessed crime sprees in recent decades that were unheard of in other points of American history. These cities are in political jurisdictions that feature stringent gun control like universal background checks and make it nearly impossible for citizens to acquire firearms.

And it’s more than just the guns. These areas are already filled with a bevy of socialist policies like public schooling, minimum wage laws, and subsidized housing that create sub-optimal socio-economic outcomes. On top of that, many urban centers have questionable policing practices and criminal justice policies that don’t effectively apprehend criminals, nor prevent them from reverting back to their criminal ways once they’re back in normal society. In turn, many individuals resort to crime in these cities as a way of making a living. Adding gun control into the mix just makes things even worse.

Northfield, Minnesota vs. Tombstone, Arizona: A Tale of Gun Rights vs. Gun Control

In 1876, 145 years ago, the Younger Gang ended their bank robbing career after a botched robbery in Northfield, Minnesota.

Any proud gun owner should celebrate when an armed citizen steps up to defend himself against criminals. Researchers like Gary Kleck point to over 2 million cases of individuals using firearms in self defense. This is no recent phenomenon though.

Law-abiding citizens standing up to criminals actually occurred on numerous occasions during the Old West. The most notable case was the failed bank robbery attempt conducted by the James-Younger Gang in Northfield, Minnesota.

The James-Younger Gang gained national notoriety for waltzing into towns and coming out with all the loot through well-orchestrated robberies. With so many robberies under their belts, their next robbery attempt in the sleepy town of Northfield, Minnesota seemed like a walk in the park. On the fateful day of September 7, 1876, the gang of outlaws would be in for a rude awakening once they entered Northfield.

The last thing these criminals expected was an armed citizenry that was willing to stand up against their devious schemes. As the outlaws proceeded to carry out their robbery, Northfield’s citizens quickly realized what was going on. Instead of turning to law enforcement, they took matters into their own hands.

The armed citizens of Northfield fired back at the outlaws and successfully killed several members of the James-Younger Gang. This incident had its fair share of tragedy when members of the James-Younger Gang killed the First National Bank’s cashier Joseph Lee Heywood and Swedish immigrant Nicholas Gustafson. However, these deaths were not in vain.

After the smoke cleared, the rest of the James-Younger Gang bolted out of Northfield, which marked one of the biggest reversals in Jesse James’ criminal career. From there, James lost considerable prestige as a criminal and would later be murdered by one of his partners in crime, Robert Ford, in 1882.

Despite the chaotic nature of the Northfield incident, armed civilians made a positive difference to thwart this criminal act. Had these citizens been disarmed, Jesse James and company would have made their way out of town with a cool wad of cash. This is definitely one story American students won’t find in their history textbooks.

Gun Control Could Not Save Tombstone

“No Guns Allowed” unless by written permission! Wyatt Earp was a lawman in Tombstone and Dodge City. The 1939 movie Dodge City portrayed an Earp character with gun “permits” as does the 1994 movie Wyatt Earp.

Although the Old West was marked by high degrees of freedom, especially when compared to present times, it still had pockets of gun control throughout certain regions.

Take the example of the infamous O.K. Corral standoff. This shooting has become legend throughout American folklore and an integral part of Hollywood Western movies. However, there is much more to this story than meets the eye. When we look past the dramatic effects and scruffy gunslingers, we see a much more nuanced picture of this event.

What many people don’t realize is that the O.K. Corral shootout took place during a dispute over gun control legislation in Tombstone, Arizona. According to an 1881 law, it was “unlawful to carry in the hand or upon the person or otherwise any deadly weapon within the limits of Tombstone, without first obtaining a permit in writing.”

This law, however, did not deter the outlaw gang of Ike Clanton, Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury, Frank McLaury, and Billy Claiborne. For them, criminal behavior like cattle smuggling and horse thievery was a way of life. No law was going to stop them – above all, Tombstone’s gun control ordinance.

The gang of outlaws were ready to up the ante with their criminal behavior once they set foot in Tombstone. From the get go, they encountered resistance from the Earp brothers – Virgil, Morgan, and Wyatt – and Doc Holliday, who were ready to stop these outlaws in their tracks. The law enforcers even demanded that the bandits hand over their guns. But much to the law enforcers’ dismay, the outlaws could not have cared less about Tombstone’s gun control laws and continued to disobey them like any seasoned band of criminals would do.

Eventually, this conflict escalated when both sides drew their firearms and engaged in an explosive shootout. Once the smoke cleared, three of the outlaws died during this confrontation. Thankfully for the citizens of Tombstone, there was an armed law enforcement presence to push back against the outlaws. However, this just goes to show that laws are not enough to prevent criminals from committing heinous acts. Armed individuals are ultimately the best first responders against criminals.

Gun control laws like those in Tombstone were not the norm in the American Frontier. That being said, there is still a valuable lesson behind this experience – gun control legislation will not magically make criminal activity nor gun violence go away. Even in a not-too-distant past, gun control legislation could not stop criminals.

Why the American West Matters

The misleading depiction of the Old West is a historical sleight of hand that not only advances false history, but also associates foundational freedoms such as gun rights with sprees of violence that never even existed. That’s why it’s so important to think critically and do thorough historical research, and recognize who owns the media companies which you’re consuming. Gun rights have historically served Americans well, providing them a means of defense against violent criminals while checking the state from embracing all-out tyranny as witnessed in present-day Venezuela.

We must remember that it’s not those who have the right ideas who win. It’s those who create the most compelling narratives who come out on top. Political outcomes are ultimately value neutral. The forces of good are not always guaranteed victory.

Americans have been misled about capitalism, Americans have been misled about the New Deal, and it’s become clear they’ve also been subject to many falsehoods about the Old West. History departments across America by and large have failed in providing their students with the right material to understand our country’s most cherished political practices. When institutions of higher learning drop the ball, it’s incumbent upon us to defend our history and culture by stepping up to ensure America has “an alert and knowledgeable citizenry” as President Eisenhower famously remarked. Learning the true story of the American Old West is one step in that direction.

Please “like”, comment, share with a friend, and donate to support The Standard on this page. Become a Patron!

Click the QR Code below to donate any amount.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts